I’ll be totally honest with you. I never really thought much about the intricate working of the mundane razor industry. That is, until AlterNet asked me to look into it.

But having done so, I think it’s a cut-throat hyper-reality ripe for satire, and probably standing on its last economic legs. Which could be made of 20 blades by now. You never know.

The Shaving Racket — How Are Gillette and Schick Getting Away with Ripoff Razors?

[Scott Thill, AlterNet]

The razor blade industry is swarming with impenetrably high-tech products and shockingly high prices — accused of marking up prices 4,000-percent more than the cost of production — making it an easy target for pop-cultural satire.

“Fuck Everything, We’re Doing Five Blades,” an Onion headline lampooned in 2004, spoofing an industry whose answer to the question of increased market share equaled more blades. “We’re standing around with our cocks in our hands, selling three blades and a strip,” harrumphed a caricature of Gillette CEO James Kilts. “Moisture or no, suddenly we’re the chumps. Well, fuck it. We’re going to five blades.”

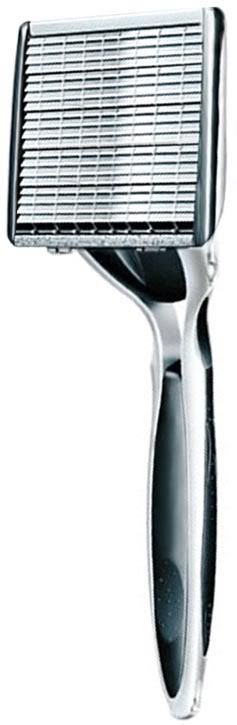

Reality trailed behind comedy in 2005, when Gillette released the Fusion, a five-blade, battery-optional super-razor with a moisturizing strip whose residue evidently soothed your skin’s post-traumatic stress disorder, or something. In Gillette’s defense, it was just responding to market pressure. Schick released the four-blade Quattro in 2003, reacting to the new environment Gillette created when it released the three-blade Mach3 in 1998. That left Gillette CEO James Kilts no choice but to up the blade count, if it was going to win the war for the global grooming market share. The real-time profit war has been won by Gillette, whose increased blade count has allowed it to charge higher prices for comparatively low manufacturing costs of razor and blades sold.

But the banal truth is that there’s a reason freebie marketing is also known the razors-and-blades model: Selling one product at a low price greatly gooses sales of a complementary product. It works just as well when it comes to printers and toner, or cell phones and network carriers. The concept is simple: Cheap product, expensive packaging, crafty marketing, and hefty profits when the customers have to replace the blades. In market analysis, parsing loaded terminology is paramount. Proctor & Gamble knows this because it once was nailed by a Connecticut judge for advertising that was “unsubstantiated and inaccurate,” “greatly exaggerated” and “literally false.”

“Gillette blades are housed within the razor cartridge and they are the engine of the razor,” a P & G spokesperson explained to AlterNet. “The Fusion ProGlide Power blades are re-engineered blades with edges that are thinner than Fusion. They are finished with Gillette’s most advanced low-resistance coating, which allows the blades to glide effortlessly through hair for incredible comfort. The blades must cut through about 10,000 to 15,000 beard hairs that are as tough as copper wire and grow in different directions. To add to the challenge, the blades must cut the hair as it is held in skin that has the consistency of jelly.”

Coating ever more thinner blades, as well as pulling the shrink ray on products whose suspicious pricing has avoided equitable downsizing, has bought P&G a profitable position in global grooming. As of its last earnings report, net sales have increased three percent, pulling in $7.6 billion for the fiscal year, on negligible volume increase.

“Price increases, taken primarily across blades and razors and in developing regions to offset currency devaluations, added four percent to net sales,” P&G’s spokesperson explained. “Operating margin increased behind improved gross margin due mainly to price increases and manufacturing cost savings.”

But the big players are under fire from cheaper disposable razors, and what P&G defines as “disproportionate growth of low-cost razor systems in developing regions.” It’s a snapshot of the industry as a whole, which has hit a high-life ceiling in uncertain financial times. Other than higher spending on marketing, or more blades, there really isn’t anywhere else to go.